At last a story for which I have personal experience to back up what I say: the story, announced in The Telegraph on 11 July 2010 that King Arthur’s “Round Table” is actually the Roman amphitheatre in Chester! A similar story (with nicer graphics, it has to be said) appeared in The Mail Online on the same day, while The Independent carried a story giving the “Top 10 clues to the real King Arthur”, by Christopher Gidlow, who appears to be the historian behind the claims and who just happens to have just published a new book, Revealing King Arthur: swords, stones and digging for Camelot (The History Press, 2010). It also happens that The History Channel has a programme, King Arthur’s Round Table Revealed, first aired on 19 July 2010, about it. So am I surprised, pleased or horrified by the announcement?

Before launching into what I think about the claims, I’d like to say what I think about his first book on Arthurian matters, The Reign of Arthur (Alan Sutton, 2004). Insofar as popular (as opposed to academic) books on the subject go, it’s considerably better than most of its rivals. Mr Gidlow is convinced that there was a real person named Arthur who lived around the year 500, around whom the Arthurian legends grew. He goes against the current consensus that Arthur was initially a figure of folklore, perhaps even a divinity; the consensus view is that an “historical Arthur” was constructed around the folkloric character as Welsh historians sought to root him in history and put him at a time when a hero who fought the English could plausibly have flourished. Gidlow turns this on its head. In his view, Arthur was a genuine character who gradually attracted legendary material; he uses the available historical sources to back up this claim, showing that the earliest sources contain very bland and mostly plausible material about Arthur, and that it is only later sources that clearly describe a character not of history but of folklore or legend. I like this approach: it treats the historical sources much more fairly than many historians do. Too many start from the High Medieval portrayal of Arthur as a king who performs feats suitable only for a legendary hero and project this back onto the earlier sources. Using this sort of logic, we could dismiss Charlemagne as a fictional character were it not for the contemporary literary and archaeological evidence for his existence, something that is clearly unreasonable. It is equally unreasonable to do this with Arthur, according to Christopher Gidlow.

What, then, is Gidlow’s evidence (if, indeed, it is not his and not an over-enthusiastic Tourist Information Centre)? As quoted in The Telegraph and The Mail Online, it is this: “The first accounts of the Round Table show that it was nothing like a dining table but was a venue for upwards of 1,000 people at a time. We know that one of Arthur’s two main battles was fought at a town referred to as the City of Legions. There were only two places with this title. One was St Albans but the location of the other has remained a mystery. The recent discovery of an amphitheatre with an execution stone and wooden memorial to Christian martyrs, has led researchers to conclude that the other location is Chester. In the 6th Century, a monk named Gildas, who wrote the earliest account of Arthur’s life, referred to both the City of Legions and to a martyr’s shrine within it. That is the clincher. The discovery of the shrine within the amphitheatre means that Chester was the site of Arthur’s court and his legendary Round Table”.

The Round Table

There is so much wrong with this, it’s difficult to know where to start, but let’s assume that Mr Gidlow has been quoted correctly (although the same quotation is identical in both sources, The Mail Online is not unknown for cutting-and-pasting from others’ articles). First off, “[t]he first accounts of the Round Table” date from the twelfth century, when an Anglo-Norman writer named Wace (c 1115-1183) translated Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Brittanię from Latin into French. He includes one mention of the Roonde Table. There are no mentions of it beforehand and no specification of the number of knights who could be seated at it.

Here is Wace’s account, in the translation of Eugene Mason, from Project Gutenberg:

Because of these noble lords about his hall, of whom each knight pained himself to be the hardiest champion, and none would count him the least praiseworthy, Arthur made the Round Table, so reputed of the Britons. This Round Table was ordained of Arthur that when his fair fellowship sat to meat their chairs should be high alike, their service equal, and none before or after his comrade. Thus no man could boast that he was exalted above his fellow, for all alike were gathered round the board, and none was alien at the breaking of Arthur’s bread. At this table sat Britons, Frenchmen, Normans, Angevins, Flemings, Burgundians, and Loherins. Knights had their plate who held land of the king, from the furthest marches of the west even unto the Hill of St Bernard.

And here, in the original Old French, from Google Books:

Por les nobles barons qu’il ot

Dont cascuns mieldre estre quidot;

Cascuns s’en tenoit al millor,

Ne nus n’en savoit le pior,

Fist Artus la Roonde Table

Dont Breton dient mainte fable:

Iloc séoient li vassal

Tot chievalment et tot ingal;

A la table ingalment séoient

Et ingalment servi estoient.

Nus d’als ne se pooient vanter

Qu’il séist plus halt de son per;

Tuit estoient assis moiain,

Ne n’i avoit nul de forain.

N’estoit pas tenus por cortois

Escos, ne Bertons, Ne François,

Normant, Angevin, ne Flamenc,

Ne Borgignon, ne Loherenc,

De qui que il tenist son feu

Des ocidant dusqu’à Mont Geu

Remember, before this poem, there are no mentions in any of the literature of a Round Table. We are talking about the earliest evidence being some 650 years after the purported date of ‘King’ Arthur. If it’s something that is so central to the Arthurian story, we need to be told why nobody thought it needed to be mentioned for centuries.

Gildas and Legionum Urbs

In The Reign of Arthur, Gidlow suggests that the notorious chapter of the Historia Brittonum purporting to be a list of the battles fought by Arthur dux bellorum (“leader of battles”) is genuinely historical. This goes against the consensus historical view that the list is a fiction, but let’s concede that Gidlow’s reasoning is correct (and, in this case, I have reason to believe that it is) and that the ninth battle, in urbe legionis (“in the city of legions”) really was fought around AD 500 by a general named Arthur. Gidlow is quite right to say that “[t]here were only two places with this title”, although where he got the idea that one of them was St Albans is something of a mystery. One of these places is still called Caerleon, in South Wales (Caerlleon in modern Welsh), and the other was Chester. It is quite wrong to say that “the location of the other has remained a mystery” when historians have agreed on it since the time of Bede in the early eighth century!

Next, Gildas’s surviving writings (de excidio Britanniae, some fragments from letters and a Penitential of dubious authenticity) do not mention Arthur, let alone constitute “the earliest account of Arthur’s life”. He does mention a “City of the Legions” (actually legionum urbis, “of the city of legions”, in the original Latin), which he associated with a pair of martyrs he names as Aaron and Julius, citizens of the place. Taken since the twelfth century (on the very dubious authority of Geoffrey of Monmouth (Historia Regum Brittanię IX.12)) to have been Caerleon in South Wales, Legionum Civitas (using the more usual word civitas (‘city’) in preference for the poetic urbs, which almost always refers to Rome) was probably used in the Late Roman period as a term for Chester. Indeed, the Old Welsh name of Chester, Cair Legion, is a direct translation of Civitas Legionum, the form in which it appears in Bede (Historia Ecclesiastica II.2). There are therefore no a priori reasons for rejecting Chester as the location of the martyrdom of Aaron and Julius.

However, the second part of Gidlow’s argument for identifying legionum urbs with Chester involves a shrine, of which there is no mention in the text. What we do have, immediately preceding the naming of Alban, Aaron and Julius, is the phrase “clarissimos lampades sanctorum martyrum nobis accendit, quorum nunc corporum sepulturae et passionum loca non si lugubri diuortio barbarorum quam plurima ob scelera nostra ciuibus adimerentur” (“he lit the most famous lamps of the holy martyrs for us, were it not that their places of death and bodily burial are taken away from us by the mournful partition with the barabarians as a result of the many sins of our citizens”). Then comes an amazing leap of deduction: “[t]he discovery of the shrine within the amphitheatre means that Chester was the site of Arthur’s court and his legendary Round Table”. How? This is worse than adding 2 and 2 to make 5!

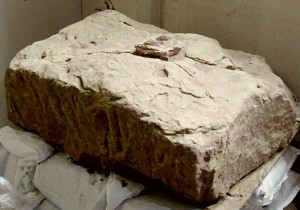

Chester’s Roman amphitheatre

It’s then quite wrong to suggest that the discovery of the amphitheatre at Chester is a recent event: it was first located by W J (Walrus) Williams in 1929 (the nickname derives from a description of his moustache!). Major excavation of the northern 40% of the site took place between 1957 and 1969, and it was opened for public display in the 1970s. I put together a Research Agenda during the 1990s, which was used to decide how and what to investigate when I started to re-excavate parts of it in 2000. I left my job with Chester City Council early in 2004, just before a much larger investigation, in partnership with English Heritage, began under the direction of Tony Wilmott and Dan Garner.

In the meantime, I had investigated enough of the monument to know that the interpretation published in 1976 was wrong on a number of counts. In particular, a series of postholes in the centre of the arena, published as part of a platform on which the legionary commander would stand while reviewing his troops or presenting them with medals, could not have been part of a platform. For one thing, the very English view that amphitheatres located outside Roman forts and fortresses were used for military weapons training and troop reviews is, quite frankly, laughable. It’s based on the silly idea that members of the Roman military elite were far too gentlemanly to be interested in such brutal entertainments as gladiatorial combat and staged animal hunts. Of course they weren’t, and I suspect than nobody outside the United Kingdom ever believed in such a patently ridiculous idea. I suggested instead that the postholes belonged to a post-Roman timber building of possibly two separate phases. In an article published in Cheshire History in 2003, I hinted that they might have been ecclasiastical structures. At the time, I could not prove their date, but the subsequent work of Tony and Dan confirmed my guess. They might be churches (not shrines), but they might equally have been the residences of Dark Age lords. Indeed, Tony and Dan’s discovery that the amphitheatre was fortified in the sub-Roman period, which I had again speculated might have been possible, makes this second interpretation more likely.

The “execution stone” is no such thing. In the centre of the arena, Dan and Tony found a large stone block with an iron ring set into it. We can speculate that animals (and perhaps condemned criminals or particular types of gladiator) would be tethered to it, giving them sufficient room to run around and provide ‘entertainment’ for the crowd as they tried to escape their armed attackers. Similar blocks were found in the arena during the 1960s excavation. Perhaps Christopher Gidlow has misread my paper in Cheshire History, where I raised (and rejected) the possibility that the postholes in the arena were elements of temporary structures used during the execution of criminals, maybe including Christians.

The Top 10 Clues to the Real King Arthur

So, I’m not impressed with this story. Do the “Top 10 clues to the real King Arthur” fare any better? The first “clue” is Tintagel, associated with the legends of King Arthur since Geoffrey of Monmouth in 1139. This is very late evidence to assume that it has any bearing on a fifth- or sixth-century character, but, as the article points out, it was occupied at precisely the right time. Of course, in Geoffrey, Arthur’s only connection with Tintagel is that he was conceived their with the help of Merlin’s magic. It is not quite true to say that “[e]xcavations demonstrated that, as the legends said, this was a fortified home of the ruler of Cornwall in about 500AD.”, as all the excavations have shown is that it was a densly occupied site at this time, but possibly more urban in character than “a fortified home”. Moreover, the discovery of a slate inscribed with the name Artognou is irrelevant and neither this nor the other names (Coll, Paternus and Maxen[tius]) inscribed on it are even remotely like “other names from the legends”. So, as a “clue”, Tintagel is worthless.

The presence of a Late Roman basilica in London, while interesting, is hardly unexpected: as the capital of the fourth-century Diocese of Britanniae, the city would be expected to be home to its principal church. That’s a very long way from confirming the idea that the young Arthur drew a sword from an anvil sitting on top of a stone there, though!

The sub-Roman activity at Silchester is also very interesting. We don’t know why Geoffrey of Monmouth made it the site of Arthur’s coronation, but again, we can hardly use someone writing more than six hundred years after the supposed event as a primary authority. Worse, to ask if there could “be a connection between Arthur’s sword, Excalibur and the late Roman name for Silchester, Calleba?” shows woeful ignorance of linguistics (the name of Silchester was Calleva, and it’s a late misspelling that replaces the -v- with a -b-) and of the origins of the name Excalibur (Geoffrey of Monmouth spells it Caliburnus and it derives from Welsh Caledfwlch, which has nothing to do with Calleva).

That “Henry VIII’s librarian, John Leland, identified the Iron Age hill fort of South Cadbury as the original Camelot” is hardly relevant, more than a thousand years after Arthur is said to have lived. Moreover, Camelot is first mentioned in Chrétien de Troyes’ poem Lancelot, li chevalier de la charette, dating to the 1170s:

A un jor d’une Acenssion

Fu venuz de vers Carlion

Li rois Artus et tenu ot

Cort molt riche a Camaalot

Si riche com au jor estut.“One Ascension Day,

King Arthur had come

from Carlion, and held

a very rich court at Camaalot,

so rich as was fitting on that day.”

It’s worth noting that this is the only mention of Camelot: it’s not Arthur’s principal court, there is no mention of a Round Table… It’s as if Chrétien is just throwing in another exotic name for the sake of entertainment (after all, he was writing fiction). So to use a librarian’s opinion a thousand years after the event to prove that a place that was actually occupied at the right time really was Camelot is a bit poor. Yes, South Cadbury has some very interesting sub-Roman archaeology, but it’s far from the only place in south-west England to have been the residence of a high status fifth-/sixth-century warlord; why single it out as the only potential Camelot?

Next, Wroxeter gets dragged out as a “clue”, although it’s hard to see why. Yes, its sub-Roman archaeology is truly spectacular, but it’s not alone in having it. Chester, too, has excellent archaeology of the period, even if it has hardly been appreciated (although we can hope that the discoveries in the amphitheatre will go some way toward rectifying this). To say that “[t]radition put the home of his wife, Queen Guinevere, at nearby Old Oswestry” is simply lame.

Chester’s amphitheatre, that poor, over-hyped and much misunderstood monument, is irrelvant to the story, as I’ve already explained. Tony Wilmott is distancing himself from the television programme, in which he appears; on his Facebook wall, he says “I am embarassed to say that I appear in this piece. My contribution has been cut and voiced over to make it appear that I support and endorse the ludicrous, far fetched conclusions that are reached. I would like all of my friends and colleagues to be aware that I emphaticaly DO NOT!”. Case closed, I think!

Heronbridge is a different issue. The excavations there by David Mason re-examined the site of a post-Roman earthwork found in the 1920s to be associated with some poorly dated skeletons. His work has shown that the bodies date from the early seventh century, a time when Bede documents a battle at Chester, fought between Æthelfrith, king of Bernicia c 593-616, and the local Welsh rulers. Nothing to do with Arthur and a century too late anyway, so why even bring it up?

Birdoswald comes next; poor Tony Wilmott must be furious, as it was his excavations here in the late 1980s that discovered evidence for sub-Roman occupation. Again, it is difficult to see why it is mentioned at all; to say that “[m]any scholars believe Camlann was ‘Camboglanna’, a now-vanished fort on Hadrian’s Wall is scarcely relevant. The site of Camboglanna was at Castlesteads, west of Birdoswald, so we have yet another non sequitur that offers no “clues” to the “historical Arthur”.

“Slaughterbridge on the River Camel has proved popular, for obvious reasons. There are numerous reports of finds of Dark Age weaponry from the site. It is now the location for an ongoing archaeological project intended to get a clearer picture of life in the Dark Ages there, and near neighbouring Tintagel. A 6th century memorial stone, inscribed in Latin and Irish Ogham, is still visible here, bearing an enigmatic inscription, probably to a Romano-British warrior named Latinus.” Can anyone explain how Slaughterbridge can be Camlann, if it is also at Castlesteads on Hadrian’s Wall and somehow also related to Birdoswald? This is irrelvance of the highest order.

Occupation on the top of Glastonbury Tor has been known since Philip Rahtz’s excavations, but it is difficult to see how this is relevant to the Arthurian story. His association with Glastonbury is not with the Tor but with the town, a short distance away. The first time we hear of Glastonbury in an Arthurian context is in Caradoc of Llancarfan’s Vita Giladae (“Life of Gildas”, the British cleric we met earlier as someone who didn’t write an account of Arthur’s reign, despite the claims of the popular press). In Chapter 10, we learn that Gildas “ingressus est Glastoniam cum magno dolore, Meluas rege regnante in Aestiua Regione… Glastionia, id est Urbs Vitrea, quae nomen sumsit a uitro, est urbs nomine primitus in Britannico sermone. obsessa est itaque ab Arturo tyranno cum innumerabili multitudine propter Guennuuar uxorem suam uiolatam et raptam a praedicto iniquo rege et ibi ductam…” (“entered Glastonia with great anguish, King Melwas reigning in the Summer Region… Glastonia, that is Glass-town, which gets its name from glass, is the town first known by that name in the British language. So it was beseiged by the tyrant Arthur with a great host because Gwennuvar his wife had been violated and seized by the aforementioned wicked king and taken there”). This is a story about the Abbey, which is not on the Tor, so once again, we are treated to some irrelevant information disguised as a “clue”. Moreover, the late date of the information in Caradoc’s Vita Gildae is obvious when we realise that Glastonbury is an English name, not Welsh, and that “the Summer Region” is just a poor translation of English Somerset into Latin!

The burial at Glastonbury has long been dismissed as a medieval fraud. We have Leslie Alcock (1925-2006) to thank for resurrecting it as a possibly genuine sub-Roman aristocratic burial. Descriptions of the discovery were written by Ralph of Coggeshall in 1221, Giraldus Cambrensis in 1193 and Adam of Domerham (himself a monk at the abbey) in the 1290s. All give slightly different accounts of the discovery of the body, but it was alleged to have lain in an ancient coffin, hollowed from an oak trunk. They also differ in the wording of the inscription said to have been on a lead cross found above the coffin. Ralph gives it as Hic iacet inclitus rex Arturus in insula Avallonia sepultus (‘here lies the famous King Arthur, buried in the Isle of Avalon’); Giraldus adds the phrase cum Wenneveria uxore sua secunda (’with his second wife Guenevere’) at the end.

In the sixth edition of William Camden’s Britannia, published by Richard Gough in 1607, a drawing of the cross appeared for the first time. It is by no means certain that Camden saw the cross, but Leslie Alcock used the shape of the letters in the drawing to suggest that it dated from the tenth or eleventh century. He was subsequently (and, in my opinion, rightly) criticised for his lack of scepticism regarding the alleged cross, last known to have been owned by William Hughes, a chancellor of Wells cathedral, in the early eighteenth century and no longer available for study. Although a Derek Mahoney claimed to have rediscovered it in the bed of a lake at Forty Hall near Maidens Brook, Enfield (UK), when it was being drained for dredging, according to the Enfield Advertiser of 17 December 1981, it is now thought that Mahoney’s cross was a forgery.

So have we been shown any worthwhile evidence?

The short answer has to be “no”. Although I will not be watching The History Channel’s clearly ridiculous “documentary” (I can watch all manner of ridiculous “documentaries” on Freeview, without having to pay for the privilege of hundreds of unwatchable television channels), I am inclined to trust the opinion of a friend who was misled by the producers into believeing that the programme was serious. The press releases put out as free advertising for the show do not inspire any confidence.

But… But this does not mean that I am completely sceptical of evidence that there might have been a British soldier named Arthur who had a series of victories over the Anglo-Saxons around AD 500. I suspect that there was a genuine character who was remembered in increasingly elaborate legends throughout the Middle Ages and into modern times. It’s that the very weak (and occasionally completely wrong) evidence that Chrisopher Gidlow has presented to us is not robust enough to do the job of resurrecting Arthur as an historical character.

As you will probably gather, the Mail article does not give a full or accurate version of my views! Top Ten Clues, on the other hand, I was responsible for, so any errors in them are mine. I’ve taken features of the legends which readers might be familiar with and pointed readers to archaeological material which may shed some light on their origins or connection with history. At the risk of saying ‘read my book’, I’ll answer a couple of points. Chris Morris and his team, who excavated Tintagel, are responsible for the identification of the site as a stronghold of the Ruler of Dumnonia c500, rather than just ‘a densely populated site’, and this is indeed what Geoffrey of Monmouth, the first person to name and describe the site, also says. Maxen, Coll and Patern are all names from the legends (Maxen in the Mabinogion, Coll in the Triads and Patern in the Life of St Patern, where he is explicitly linked with Arthur). Now, what we are to make of these facts are a matter of debate and speculation, and it may be, as you suggest, they have no meaning beyond coincidence, but I hardly think it is bad archaeology to raise them as possible routes for further investigation.

‘Revealing King Arthur’ does not claim to reveal King Arthur but looks at various attempts by archaeologists in the last fifty years to reveal or deny Arthurian connections while, I hope, showing which findings can be taken as supporting the positivist case in ‘The Reign of Arthur’.

LikeLike

Chris

Many thanks for being the first person to comment on this post. I had suspected that most of the press hype was just that: your first book was too carefully argued for me to believe that you had suddenly done a poorly-researched follow up. As you must have guessed, my starting point was the claim about Chester’s Roman amphitheatre, which was something very close to my heart for some years and for which I can be blamed for first highlighting its sub-Roman significance.

I take your point about Coll and Paternus, though I think that the first name may well be Coliaw, but we really can’t transmute Artgonou into Arthur. That was the real point of Chris Morris’s complaint about the popular press.

I will also read your book (I’m ashamed to admit that until The Independent article, I wasn’t even aware that it existed, and I usually keep an eye open for Arthurian related stuff). Do you plan a scholarly version, perhaps combining the two?

But I must say that I’m flattered that you were the first commenter on this rather over-long article. This is the wonderful thing about the web!

LikeLike

Keith

I love the website, just rather taken aback to find myself castigated on it! I wrote the top 10 piece for Heritage Key website, which History Press uses to publicise its books. There’s an extract of my chapter on the Artognou stone on the site too. What I was trying to do was pick aspects of the legends which are generally known and draw attention to archaeological links which have been made to them. Thus, although you are perfectly right about Arthur and Glastonbury Tor, Rahtz specifically wrote, in 1968, regarding his excavation, ‘If we wished to put a name to the chief of Glastonbury, it would be Melwas’. Francis Pryor in 2004 wrote ‘if ever a place demanded an Arthur it is surely post-Roman Wroxeter, but his name has never been linked to it.’ Never say ‘never’. Michael Wood linked it in ‘In Search of the Dark Ages’ and Philips and Keatman did in ‘King Arthur – the true story’. The Shropshire local government website now boasts a King Arthur trail around it, taking in sites like the Guinevere birthplace at Old Oswestry.

The material about the size and construction of the Round Table comes from Layamon’s Brut, roughly contemporary with Wace and similarly drawing on the fame of the table among the Britons.

My point about the Tower Hill Basilica, which is extensively covered on the Heritage Key website, is that archaeologically the 5th/6th century British identity is characterised by Christian remains rather than (as you might deduce from post ‘Mists of Avalon’ Fiction) pagan ones. I’ve no doubt that the sword in the stone and anvil is fictional, but the link to a large Roman Church is easier to support than, say, Pryor’s idea that the late 12th century story has some connection to Bronze Age forging practices.

Some amateur Arthurians have indeed argued a link between Caliburnus and Silchester (‘ex Caleba’ is my cod suggestion, sorry). Not very likely, granted. The form Caleba is not a misspelling, though. It is likely to be the way the compiler of the Ravennna Cosmography vocalised the name. As he was working c700 he is possibly closer to the Arthurian period than the sources giving ‘Calleva’. In the two earliest forms of the sword’s name Caliburnus and Caledfwlch you can see the b/v mutation taking place.

I am pretty sure that Chretien’s Camalot is Camalodunum, which he would have known as an ancient British Oppidum from Pliny’s Natural History. It’s identity as Colchester was only established in the 18th century. You are quite right that South Cadbury has no medieval pedigree. In the printed version of the Morte Darthur Malory says Camelot is Winchester and Caxton that it is in Wales. The fact that South Cadbury is now firmly identified as Camelot in most popular works is entirely due to Lesley Alcock and the (bad?) archaeologists of the Camelot Research Committee.

One last point. It is now quite commonplace to identify the ‘Arthurian’ battle at the City of the Legion with the early 7th century battle there reported by Bede. Inferences drawn are a) Arthur is a later figure, wrongly credited with the Battle of Badon, b) an early figure wrongly credited with the battle at the City of the Legion or increasingly c) Arthur is a ficticious character wrongly connected with both battles. I see no reason for there not to be more than one battle of the City of the Legion, a British victory followed by a Saxon one. Annales Cambriae thought there were two battles of Badon, for instance. The range of carbon dates for the Heronbridge Northumbrians would easily admit to a battle before Bede’s one. More-over the fact they seem to be buried with Christian practices (West/east aligned without grave goods), despite their origin in pagan Northumberland, might indicate that the field was not held by the pagan king AEthelfrid but by the British, hence presumably before the Anglian victory described by Bede.

LikeLike

wonderful effort,thank you!Can’t find much to comment on ,,skepticism really doesn’t come into play anywhere,a great example of “non linear thinking”?with thorough research .!Remember my claim of a Neolithic Artisan culture, carvers of stone that settled the Tararua District 5-15 million years ago .These carved stones have been verified at that age by .G.N.S. and John Hayes M.P…Bruce McFadgen.Hamish Cambell have indicated they are on their way for a gander ..!But i doubt it will happen ..?

LikeLike

Chris

Thanks for taking the time to post such a lengthy reply. I tried to make the post look as if I wasn’t sure who was to blame for the silly press hype: if it needs beefing up to make it clear that you’ve been misrepresented by The Daily Mail and The Daily Telegraph, I’m happy to do so.

With Rahtz’s comment about Melwas, we’re on the same sort of ground as Alcock being happy to use the name Arthur if he thought it would draw more attention to South Cadbury. If we want to believe in Melwas, then we have to associate him with the town and abbey; if anyone wants to make Glastonbury Tor his citadel, then they need to present good reasons for relocating him. I’m surprised that Francis Pryor hadn’t come across Phillips & Keatman when researching Britain AD, but perhaps that’s the difference between academics and popular writers: they barely acknowledge the existence of each other (and it’s a two way process: popular writers seem blithely unaware of Dumville’s critiques of the ‘Nennian’ authorship of the Historia Brittonum, for instance).

Yes, I agree that the Christian aspects of the period often get washoed over by all the horrible New Age/neo-Pagan writing, so the Tower Hill basilica is important. Interestingly, there’s what seems to be a sixth-century Christian cemetery in Hitchin (where I live) that develops as the very pagan cemeteries of sub-Roman Baldock, just a few miles away, go into decline. In looking at Anglo-Saxon paganism in the east, we forget that there must have been a ?majority Christian British population among whom the immigrants lived.

I have to disagree about the name Calleva, though. The form in the Ravenna Cosmography (Caleba Arbatium) shows a typically Late Antique orthographic error, with conosonantal –u– (not –v-!) miswritten with a softened –b-. The Brittonic original *calleua must derive from the same root as modern Welsh celli, which would be *calli-, meaning ‘wood’. Brittonic intervocal –u– did not develop into –b– but into –gu-. As for Caliburnus>Caledfwlch, the first element of the Brittonic name must be *caleto-, completely unrelated.

I’m interested in the idea that the radiocarbon dates from Heronbridge might support an earlier date for the battle victims. It’s some time since I last looked at them, but my recollection is that they seem pretty definitely early seventh century. And if the burials appear to be Christian, wouldn’t that be the local Christian population (with their bishop at Chester) burying their own dead? After all, Æthelfrith’s victory didn’t bring Cheshire under Northumbrian control…

And yes, there’s no reason at all why there shouldn’t be an Arthurian battle of Cair Legion followed a century or so later by a battle of Carlegion/Legacaestir!

LikeLike

Keith, I’m so pleased you’ve written this (and that Mr Gidlow has been able to respond so generously). I was putting together something myself but it would have been less informed and also less balanced. I hope the debate can continue!

LikeLike

What about BAD PHILOLOGY? Lots of websites claim that the ‘real Arthur’ was Ambrosius Aurelianus, referring to – whom do you think? – Nennius and Geoffrey of Monmouth! :-))))) The only problem is that both name Arthur and Ambrosius as definitely separate characters…

Isn’t that childish – willing so much that all the tales were real? What is next – a scholarly biography of Cinderella?

LikeLike

We were “fortunate” enough to watch the Arthur special on the Hack-story Channel, and all I can say is it’s nice to know that I wasn’t the only one out there yelling “Aww, COME ON!” at the screen. At least figuratively.

Thank you for shining the light of logic, rationality, and >GASP< scientific objectivity on the senationalistic tripe that the History Channel vomits all over the airwaves.

We watched another winner last night:

http://www.history.com/shows/the-real-face-of-jesus/articles/about-the-shroud-of-turin

Oh, man… this was bad. This was really bad. There was NO skeptical voice on this show at all. And while there was some excellent 3D design on display, some of the logical leaps were truly titanic.

An example of my personal favourite:

"We can't explain what made the marks on the shroud, but they look like shadows, so they must be made by light, but the light couldn't have been white light because it didn't scatter, but it couldn't have been laser light because it wouldn't have burned in a shadow pattern. Thus, it must have come from within the corpse, but not all of the light could have made it out. Thus, when Jesus ascended, he captured some of the light and took it with him to wherever he went."

Yes. I'm not kidding.

Can we get some Bad Archaeology lovin' on this one please? I need to know if anyone else saw this pathetic attempt to give christian fundamentalist propaganda some sort of scientific credibility.

Sorry for the rant, but I needed to evacuate the festering brain-boil that show left in its snail-slime wake.

LikeLike

Thanks Keith, for this very cogent and extensive piece. I can’t add any more. Your quote from my Facebook page is indeed my position on the TV programme.

The ‘martyr’s shrine’ in the amphitheatre at Chester was invented by the film-maker. He cut some things I said out of context and then built on it by voice-over to fictionalise and sensationalise the archaeolgy.

I can’t help but note the irony that the Caerleon amphitheatre was colloquially known as ‘King Arthur’s Round Table’ before it was excavated. Mortimer Wheeler’s excavations were funded by an American organisation known as the Knights of the Round Table, and the Daily Mail (!)on the back of the specious Arthurian connection.

You are right to say I’m not happy. As soon as the sub-Roman buildings at Birdoswald emerged I had press stories concerning Arthur thrown at me. I issued accurate information, but as usual in this context it was ignored. That the list of clues to Arthur includes Chester and Birdoswald is, as you say, not good. At the best it is lazy.

By the way, until 1976 Birdoswald was thought to be Camboglanna. It was was in ’76 that an omission in our received version of the Notitia Dignitatum was realised and Camboglanna was correctly located at Castlesteads and Banna at Birdoswald (it was O.G.S. Crawford of all people who speculated in ‘Antiquity’ that Camboglanna might be identified as Camlann). At the time Carlisle was being touted as Camelot, invoking the battle of Arthuret and the whole northern Arthur idea. I remember joking – in sheer exasperation – that Arthur might have been at Carlisle, Mordred at Birdoswald, and they both set out along Hadrian’s Wall in opposite directions to meet at Castlesteads\Camlann. Now I’ve put that joke here I wouldn’t be remotely surprised to see it picked up and used in future Arthurian speculation!

Further irony – I visited the Cadbury Castle excavation in 1968, when I was 12 years old, and that was where I decided I wanted to be an archaeologist. The association of Cadbury with Camelot, as you say invented by Leland, was used by Alclck and Mortimer Wheeler again, to attract funding for their excavation. Wheeler was simply repeating what had worked previously at Caerleon.

What I deeply regret is that the Arthurian gloss (almost an Arthurian media industry)that infects the sub-Roman period in Britain like a plague, obscures some really interesting new evidence for a facscinating and important historical period about which we can now start making real conclusions and developing real ideas. As long as film-makers and others show sufficient contempt for their audiences to assume that they will not be interested in this research without Arthur coming into it, we will be fighting a losing battle in conveying this crucial period of British history to the public to whom it belongs.

Best

Tony

It seems that

LikeLike

At the risk of stretching this out beyond its natural lifespan, I am very puzzled to find ‘Top 10 clues’linked with fanciful Turin Shroud material and other ‘bad’ archaeology. I tried to make it unexceptionable, except if you are commited against any consideration of a historical Arthur. The clues are fairly well known sites which have been linked to well known aspects of the Arthurian legends, and all the links are couched as ‘maybes’ or have question marks after them. I specifically say that Camboglanna is now identifed with the next fort to Birdoswald. I hardly think it is ‘lazy’ to include the Birdoswald site as a potential ‘clue’. Francis Pryor in ‘Britain AD’, commenting specifically on Tony’s excavations, wrote ‘If one is looking for a job description for an early fifth century Arthur-like figure, the post Roman commander at Birdoswald would be an almost perfect match’. Is he a ‘bad archaeologist’?

Lumping together the supernatural physics of the Turin Shroud with contested (neither proven nor unproven) sites for Annales Cambriae’s ‘Gueith Camlann’ is too wide a net for ‘bad archaeology’. In 1950 saying South Cadbury was a subRoman site would be ‘bad archaeology’, saying in 1980 that Tintagel was a 6th century secular site, or in 1960 that Camboglanna was Castlesteads, equally so. 5th/6th century Britain is full of uncertainties, or sites intrepreted by prevailing archaeological fashion. This is very different from the majority of clearly falsifiable ‘bad archaeology’ on this invaluable website.

Camlann looks like it should be *Cambolanda’ (crooked enclosure) rather than Camboglanna (crooked glen). Geoffrey of Monmouth had the battle name in the earlier form of Camblan. He thought it was in Cornwall, presumably the Camel. As there is a 6th century inscribed stone there, this seems a reasonable ‘clue’, presenting the regional disputes which are common in Arthurian material. It is surely more relevent than irrelevent to the search for clues that there are competing and in this case incompatible identifications of the legendary sites.

We are probably in agreement that the sensationalist presentation of all archaeological excavations on the Television as groundbreaking paradigm-shifting revelations is not reflective of the reality of work done. ‘Top 10 Clues’ was my attempt (and well received other than on this site) to widen the discussion beyond ‘Chester was Camelot’, with routes which generally interested readers could follow. Heritage Key links to articles on its own site about, for instance, Birdoswald.

I am happy to stand alongside ‘good’ Archaeologists like Sir Mortimer Wheeler as an Arthurian positivist. The knee-jerk reaction currently raised against any linking of Dark-Age sites to Arthurian material is just as unhelpful when trying to connect with the general public than wide-eyed acceptence of any medieval legends. I am for striking a balance between these extremes.

LikeLike

Chris

I think that part of the ‘badness’ is that while the Top 10 is fine as a list of sites with potentially Arthurian connections, it doesn’t perform so well as a list of sites providing evidence for an historical Arthur.

Tony’s accusation of laziness, I suspect (and I haven’t asked him), is more to do with the invalid equation of Birdoswald with Camboglanna and thereby with Camlann, which still appears occasionally in the popular literature. Ken Dark has made a reasoned argument in favour of a fifth-century refortification of Hadrian’s Wall, so it ought to occasion no surprise that Birdoswald has occupation at the right period for an historical Arthur. But so does Vindolanda, so does (I believe) Housesteads and probably most of the other fort sites on and around the Wall. That doesn’t, in my view, provide any clues to Arthur. And, yes, Francis Pryor’s Britain AD was definitely a bad book: in theory, it was a good idea for a prehistorian to look at the first millennium AD in a prehistoric way, teasing out the patterns and seeing continuity in the way that prehistorians can, but at the same time, his lack of understanding of the documentary history of the period caused more than a few gasps of breath among historical archaeologists.

I agree that the Top 10 list is of a very different order from the usual sort of Bad Archaeology, consisting as it so often does of people with a very clear agenda to subvert our understanding of human development. As you know, I’m no Arthursceptic and I believe that there is evidence that there was someone of that name, around that time, whose memory became fixed in legends. How much we can say about him is still up for grabs, despite the best efforts of some academics to deny his existence outright on very weak grounds (“Bad History”, perhaps?).

The basis of the story was the Daily Mail article about Chester’s amphitheatre being the “real” round table, which is plainly silly. I brought in the Top 10 list in the hope that it might shed some light on how the Mail had distorted what you wrote (and it’s quite plain that they have badly twisted your words). Nevertheless, for the resons outlined above, I think it’s better viewed as a Top 10 sub-Roman elite sites or Top 10 sites with potential links to the Arthur of legend. The knee-jerk reaction comes from the horrors that are perpetrated by the popular press as soon as there is any linking of a site with the name Arthur.

I’m worried about relying on Geoffrey of Monmouth for anything; I suspect that he knew even less about the context of an historical Arthur than we do and simply made up the details. It’s a ripping story, but then so is his account of the supposed prehistoric kings, which are constructed entirely from early medieval genealogies. If he’s capable of that sort of indisputable fiction, he’s equally capable of a similar level of fantasy around Arthur.

I hope that archaeology is (generally) positivist: we’ve mostly moved away from the terrible post-modern relativism that infected the discipline during the 1990s.

LikeLike

The problem there is that finding plausible contexts for a historical Arthur is not the same as demonstrating his existence. Sub-Roman Britain provides plausible contexts for placing many many narratives, including some of the best historical novels I ever read. If you start with the axiom, “there probably was an Arthur behind the stories” then yes, Birdoswald or many of the other Top Ten clues could apply to him; but if there was a commander at Birdoswald, and also someone able to call troops to Cadbury, a lord of Tintagel, a prefect of Londinium and so on, then all but one of those places are not evidence for Arthur, but for someone else at the same time as Arthur doing a similar job. Unless, like Nennius or Geoffrey, one applies a species of Occam’s Razor and decides they must all have been the same man! But, without that, what you’re putting forward in that article could as easily be read as “Clues to the Top Ten ‘Arthurs'”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

how thought provoking every ones comments are,it is humourous to note that today as

it was in yesteryears people will,manipulate the truth to tell a good yarn, albeit it to please an audience

and get paid as well!

maybe there is some truth out there

can you expalain these place names

for me. as i have always wondered if there was a connection, but i have never known any one to ask,

tintagel cornwall.

tegeingl sir fflint

avalon?

caeraffalach sir fflint

sir fflint next door to caer (chester)

has any one done an investigation on these

place names?

LikeLike

I’m still surprised that no one has brought Line 971-972 of “Y Gododdin” into this discussion.

Now, granted, it is a memorial epic rather than a history, and it does only exist in a 13C reconstruction of a contemporary source (Aneirin), but to my mind it is still only “smoking gun” reference to an actual historical Arthur that we have.

Here is the quote in full, lifted directly from the Welsh Classics side-by-side translation of the poem:

“[Gwawrddur] fed black ravens on the rampart of a fortress, though he was no Arthur.”

This would be tantamount to a modern spectator saying, “Schwartzkopf kicked the crap out of the Iraqis in 1991, but he was no Montgomery”.

I think that this is the one piece of incontrovertible evidence of an actual HISTORICAL Arthur… the problem is no one is quite certain what “Arthur”, as it appears in the text actually means. Is it a name, or a title?

I personally am fully willing to admit that there was a historical Arthur. Just like I am fully willing to admit that there was a historical Jesus. But, just as I feel the “modern Jesus” is a conglomerate of apocalyptic Judean preachers in the first century, so I also feel that the “historical Arthur” is a conglomerate character dredged from the collective effort of the people of Cornwall/Wales/Rheged against the rising influence of Saxon kings.

Thus the comparison between dubious Turin and Arthurian claims. Trying to find a historical Arthur is like trying to find a historical Jesus… you are always going to see what you want to see. It is a cycle that exists and has been repeated over and over again throughout history… people want to be able to point to a precedent for their beliefs. Be they religious (Jesus), nationalistic (Arthur), or artistic (da Vinci), we always run the risk of interpreting more within the data than actually exists.

Thus I get to the point of my earlier vitriol-laced tirade: the modern media hinder rather than help this dialogue… they see that people WANT to believe, so they take works like Mr. Gidlow’s book (which admittedly I have not read) and pump it full of sugary preservatives for mass consumption.

This is BAD ARCHAEOLOGY.

I truly believe that we need to stop this trend for target-based archaeological research. If we set out to find Arthur, we are going to find him. It is human nature. And in our zeal, we may misinterpret or even annihilate some REAL archaeology that may have provided REAL breakthroughs in our understanding of Britain at the turn of the 6th century.

LikeLike

There are a few ironies in the comparison by Kevin of

“[Gwawrddur] fed black ravens on the rampart of a fortress, though he was no Arthur.”

with

“Schwartzkopf kicked the crap out of the Iraqis in 1991, but he was no Montgomery”.

I wonder if they are deliberate:

1. Would Schwartzkopf’s countrymen really use a British general as a comparison?

2. Montgomery never fought Iraqis, or any Arabs as far as I know.

3. Schwartzpof has a clearly German name. The Germans were Montgomery’s enemies.

If the Gododdin excerpt is as complicated as this modern example, what hope do we have of concluding anything about the “real Arthur” from it?

LikeLike

I love your site! I got to it looking for a reference about Amphitheatres and found this. I did a paper for university on Chester Amphitheatre and its nice to know some of the conclusions I came to you have also come to. I thought that the post hole structure in the arena could also possibly be a pons, another item of arena furniture. I see that this is dated later now but I guess I was looking for evidence to seperate the legionary amphitheatre from a parade ground.

Thanks for the interesting read, i will keep checking back for new insights into bad archaeology!

LikeLike

Respected Web Master,

I found your great archaeology resource https://badarchaeology.wordpress.com

Great Work excellent presentations. I like very much very much.

I have more interesting in archaeology. I have two archaeology resource site.

Please Welcome Our archaeology site

1) http://www.greatarchaeology.com

2) http://archaeologyexcavations.blogspot.com

If you link our site please enter your comments and please provide our site url from your great archaeology site resource.

Thank You,

Regards,

Archaeology excavations

LikeLike

I’m glad someone has taken the time to engage with the absurd arguments in support of the bogus Arthurian connection with Chester. Whether Arthur really existed or not, nothing can be said about him with certainty if it isbased on gross misreadings of the original sources and a complete ignorance of, or unwillingness to admit to, the nature of those sources and the contexts in which they were originally written. Unfortunately, serious Arthurian scholars tend to regard Gidlow-type witterings as beneath their notice and don’t take the trouble to refute them, so the hapless general public is left with the impression that anything-I-tell-you-while-sitting-in-front-of-a-shelf-full-of-books is true. Mr Gidlow should go back to playing at Henry VIII – that can’t do no harm if it don’t do no good, as they say in our part of the world.

LikeLike

As we Yanks say, “must be a British thing….”

LikeLike

“I am pretty sure that Chretien’s Camalot is Camalodunum, which he would have known as an ancient British Oppidum from Pliny’s Natural History. It’s identity as Colchester was only established in the 18th century.”

Perhaps only officially “estblished” then, but believed by many to be so earlier. See the fourth book of “Holinshed’s Chroncles” where Holinshed himself tends to accept the identification of Camalodunum with Colchester ( http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/16536 ):

“But now there resteth a great doubt among writers, where this citie or towne called Camelodunum did stand, of some (and not without good ground of probable coniectures gathered vpon the aduised consideration of the circumstances of that which in old authors is found written of this place) it is thought to be Colchester. But verelie by this place of Tacitus it maie rather seeme to be some other towne, situat more westward than Colchester, sith a colonie of Romane souldiers were planted there to be at hand, for the repressing of the vnquiet Silures, which by consent of most writers inhabited in Southwales, or néere the Welsh marshes.

“There was a castell of great fame in times past that hight Camaletum, or in British Caermalet, which stood in the marshes of Summersetshire; but sith there is none that hath so written before this time, I will not saie that happilie some error hath growne by mistaking the name of Camelodunum for this Camaletum, by such as haue copied out the booke of Cornelius Tacitus; and yet so it might be doon by such as found it short or vnperfectlie written, namelie, by such strangers or others, to whom onelie the name of Camelodunum was onelie knowne, and Camaletum peraduenture neuer séene nor heard of. As for example, an Englishman that hath heard of Waterford in Ireland, and not of Wexford, might in taking foorth a copie of some writing easilie commit a fault in noting the one for the other. We find in Ptolomie Camedolon to be a citie belonging to the Trinobants, and he maketh mention also of Camelodunum, but Humfrey Lhoyd thinketh that he meaneth all one citie.

“Notwithstanding Polydor Virgil is of a contrarie opinion, supposing the one to be Colchester in déed, and the other that is Camelodunum to be Doncaster or Pontfret. Leland esteeming it to be certeinelie Colchester taketh the Iceni men also to be the Northfolke men. But howsoeuer we shall take this place of Tacitus, it is euident inough that Camelodunum stood not farre from the Thames. And therefore to séeke it with Hector Boetius in Scotland, or with Polydor Virgil so far as Doncaster or Pontfret, it maie be thought a[Page 489] plaine error.”

That Camulodunum was not identified with Colchester until the last 18th century is just not true.

LikeLike

As an amateur of archaeology I appreciate your incites into several media hyped phenomenon that get great attention. I also enjoy your prose and your logical explanations.

LikeLike

Good stuff from Jim Allen about Colchester/Camalodunum. The 18th century establshment of their identity was the answer Colchester Museum gave when asked about their interpretation of Camelot/Colchester. I don’t know what they regarded as definitive, I was assuming an inscription recovered archaeologically rather than textual analysis.

The 16th century writers had the advantage over Chretien of having Tacitus available. My feeling is that if Chretien had wanted to place Arthur in Colchester specifically he would have used the modern name. If Arthur really had been connected to Colchester (as John Morris argued in The Age of Arthur)I would expect this to have come up earlier, for instance in Geoffrey of Monmouth.

On Nesta’s main point, who are those serious Arthurian scholars? If ‘serious Arthurian scholars’ will only engage with other ‘serious Arthurian scholars’, but no tenured academic will advance a pro-Arthurian argument, then we are stuck in a loop. The whole point of my book is to raise the need for just such engagement. Short of tracking down the variorum reprint of Dumville’s article, the interested reader of, say, ‘the Age of Arthur’ or ‘Arthur’s Britain’, will never be able to find out why there is no mention of Arthur in modern archaeological literature, let alone form an opinion on whether that rejection is valid. Would Nesta like to point us in the direction of the serious Arthurian scholars who are engaging with this debate, please?

LikeLike

Ya know,..I’ve read the posts of both people here,Chris and Keith,and just wanted to say that though it is a very interesting set of arguments for either side on the issue,there will never be a “True Story of King Arthur”.Simply because no matter what is dug up,it can never be proven without a doubt that “King Arthur” of the Legends ever lived. That’s like saying that Tristan lived.Some say yes,and some say no.

Though,personally,I keep hoping that some irrefutable item will be found to prove Arthur as Guenevere’s King,it wont happen. Dont you think that the name Arthur could belong to anyone besides our one Hero King? I am sure there was more than one person with that name who was a warrior,etc.

Think about it.I’m no great scholar or anything.but I have been into the Arthurian Legends all my life,and have visited several of the supposed Sites for him,including Glastonbury,Caerleon,,and others.

Anyway,..just my take on all this. :)

LikeLike

Well, it was a bit of luck that I came across this Keith and fantastic that Mr Gidlow did too! Interesting stuff! Have you read the second book yet?

Mak

LikeLike

I have read the book. It’s not a bad overview of fifth-/sixth-century archaeology, though I have to say that I felt that Chris Gidlow could have made a bit more of some of it. I think that his first book does a much better case of presenting evidence in favour of an historical Arthur who later attracted legendary tales; it’s probably his background as an historian rathern than an archaeologist that makes the presentation of document-based data so much more convincing than the use of archaeological evidence to suggest that it might be associated with Arthur.

LikeLike

“We don’t know why Geoffrey of Monmouth made it the site of Arthur’s coronation, but again, we can hardly use someone writing more than six hundred years after the supposed event as a primary authority”.

Archaeologists do the same thing, do they not?

LikeLike

RE: Badon and Chester:

> a) Arthur is a later figure, wrongly credited with the Battle of Badon, b) an early figure wrongly credited with the battle at the City of the Legion or increasingly c) Arthur is a ficticious character wrongly connected with both battles

… Isn’t there a fourth possibility? Arthur could be an historical figure (of whatever period), but wrongly connected with both battles.

LikeLike

Why can’t archaeologists play nice? It’s the same with the letters page of Current Archaeology. Everyone is always blunt and fractious. The actual post is so derisory against Chris’ work, that I was surprised by his even handed replies. Is it not possible for an archaeologist to say “I don’t find there is enough evidence to support this theory” instead of “There is so much wrong with this, I don’t know where to start!”

Does learning archaeology mean that social skills get forced out of the brain?? Oh for a golden age of Archaeology, when things can be debated, politely, and not just bickered over.

I personally fail to see how anyone can argue one way or the other about the “facts” of anything from the Dark Ages. Unless you can dig it up in context from the period, I wouldn’t be accepting of any written word from any time during or after the Dark Ages, even if they do give names.

LikeLike

“everyone’s always blunt”: would you prefer it if everyone pussyfooted around, pretending that they all get on and avoiding criticising egregiously ridiculous ideas for fear of upsetting those who hold them? That’s not how things work in academic debates. One has to be honest, point out the ideas that don’t stand up to scrutiny and take it on the chin when the other side responds.

Chris Gidlow provided some remarkably gracious comments in reply. In his defence, I wrote the piece based on some newspaper reports that were in turn based on a short summary he had provided. There is a lesson to be learned there: when presenting a case based on alleged archaeological evidence, make sure that if the press gets hold of it, they don’t run it with a completely different spin. And that is all but impossible to do. The media have their own ways of working and many an academic has been badly bitten in dealing with them.

As it happens, I agree with a lot of Chris’s ideas: I disagreed vehemently with what the newspaper reports attributed to him. If you read my “conversation” with him, you’ll see that we agree that the blame for the silliness of the newpaper articles lies squarely with the newspapers. My starting point was the plainly ridiculous claim, made by the journalists, not Chris, that the Roman amphitheatre at Chester was the original Round Table. I spent four summers directing excavations on the site, so I know it well and was angered by this complete misrepresentation of a monument that nevertheless has a very significant sub-Roman history.

My motivation is not nastiness. Rather, it is my passionate love of archaeology. Like a devoted partner, I rush to its defence whenever I see it being wronged by unworthy suitors.

LikeLike

tommy rainey i have founded king author in have found his familey cemerty found round table a stone henge 18 ships arthurs nights 4 castles and found egpt and rome all over georia and bign picture on stone mountain and found artifact from georiga to cailforna and king arthur rooled the hole country

LikeLike

Pardon?

LikeLike

Dear Mr Fitzpatrick-Matthews,

Ref – Arthurnet post

Finding Merlin UK 2007 USA 2008

Finding Arthur UK & USA 2013

And Chris Gidlow’s Arthur was…?

Mine is at least real – Arthur Mac Aedan, c.559 to 596CE.

Archaeological evidence? Stirling tends to be omitted – I have attached a piece from The Herald newspaper, 2011.

Forgive me if I come a across as a bit chippy – but the blinkered view of those who favour a southern Arthur put on is… wearing. Guy Halsall’s book, for example, was a joke. About a dozen maps of Britain and about ten of them did not even include Scotland.

When I first wrote to Arthuriana I asked – what kind of evidence will do? Never got an answer – just, in due course, abuse and reaffirmation after reaffirmation that Arthur was whatever the particular ‘scholar’ thought the consensus was.

(I am a lawyer – Steve McQueen said in The Magnificent Seven ‘We deal in lead, friend’ – I say ‘I deal in evidence’ – and they say I am not well versed in the classics!)

One Arthurnet contributor said that the best piece of evidence for a southern Arthur is The Elegy for Geraint, when, in fact (if I am right) this is the exact opposite – it is evidence for a northern Arthur, and Arthur Mac Aedan to boot.

I did not send him my response because, as Stephen Fry said,

“Information is all around us, now more than ever before in human history. You barely have to stir yourself to find things out. The only reason people do not know much is because they do not care to know. They are incurious. Incuriosity is the oddest and most foolish failing there is.”

Best wishes,

Adam

Adam Ardrey

http://www.finding-merlin.com

LikeLike

it was the eliptical building in chester which had been built for that purpose for years look it up, it even has a store for the wagons,just lok at the plans,in the great mans book,not that you will find it in the britishmusium they could not find there arse with both hands,i say with great remorse m,t, byers

LikeLike