I’ve described my direct interaction with dowsing in a previous post. The semi-serious hunt for the eighteenth-century Cheese Warehouse on the bank of the River Dee in Chester yielded equivocal results: we “identified” a rectangular “anomaly” that most of us agreed upon. The problem was that the one wall we identified that lay on a line predicted by dowsing also lay under a bank that may have been a visual prompt for the responses we got. What was surprising was that I had not believed that the wall of the warehouse lay so close to the river bank. The subsequent location of the wall in this trench (actually a metre or so east of the line indicated by dowsing and also east of the flat top of the bank, which carries a footpath) occasioned some surprise and was seen by some of the team of volunteers (not least the member who has brought the equipment to site) as a confirmation of the reality of the technique

Now, I don’t think that it’s unnecessarily cynical of me to suggest that something other than the detection of some buried drystone masonry by means of dowsing was going on here. We had dug a linear trench at right angles to the line of the western wall of the Cheese Warehouse–wherever that may have lain–and would have hit it at some point along its line. The fact that we did has more to do with what we already knew about the location of the building from historic maps than from any use of bent coathangers swivelling in empty ballpoint pen tubes. Of course, it was difficult to persuade the rest of the team that they had not necessarily been witness to a confirmation of the reality of archaeological dowsing. It didn’t seem to matter that dowsing failed to locate the south-eastern corner of the Warehouse (the trench dug over the suggested position turned out to be well inside it) or that the wall we did locate was off the line by around a metre. No, the willingness to believe outweighed the evidence of excavation. I’m not suggesting that the team of diggers from the Chester Archaeological Society was especially credulous; no, they were simply prone to the usual human fallibility of confirmation bias.

Stapleton’s Field henge and the involvement of a well known dowser

Moving on ten years, I had changed jobs. The Cheese Warehouse was a distant (and still, to my shame, unpublished) memory and I had returned to the part of the world where I grew up: North Hertfordshire. A local group of enthusiasts – Norton Community Archaeology Group – had been formed in 2007 to investigate the heritage of one of the three historic parishes that make up Letchworth Garden City. I was asked to provide the Group with a wish-list of ten sites I considered worth investigating. One of them was actually a landscape that appeared to consist of a series of Bronze Age monuments in a field known as Stapleton’s Field (a recent name: its historic name seems to be unknown). They included a group of ring ditches (all that is left after round barrows have been ploughed flat), a possible trackway, an enclosure and a series of probable field ditches. This was exciting, as it appeared to be a nearly complete landscape from around 4000 years ago. The more I looked at aerial photographs and a geophysical survey of one of the ring ditches, described as a “double ring ditch” by the Historic Environment Record for this specific monument, the more convinced I became that something was wrong with the description. Rather than an unusually complex burial mound, I thought it looked like a henge.

A henge isn’t necessarily what you might think it to be. On hearing the word, most people think immediately of Stonehenge, a unique monument that is one of the most instantly recognisable sites anywhere in the world. There is a henge at Stonehenge, but it’s not the stones: it consists of the circular bank and internal ditch that forms the defining edge of the monument. To an archaeologist, this is what makes a henge. While some may contain stone circles, the majority do not; in some, the stone circles are a secondary addition. The henge I suspected might exist in Stapleton’s Field is one of those that did not have a stone circle, largely because the local chalk bedrock is quite unsuitable for use in megalithic construction.

To test my ideas, we dug a trench across the centre of the monument in 2010 as well as two others across anomalies seen in the geophysical survey that I thought belonged to the Bronze Age landscape I had hypothesised. The enclosure turned out to be Romano-British, as did the field ditches; the potential henge turned out to be Neolithic, although we did not find conclusive evidence for its interpretation as such. However, there was enough to go public with the idea that it was likely to be a henge, as we had found Grooved Ware pottery in the centre of the monument.

It was shortly after we had a number of stories on the radio, television, the press and the Group’s blog that the Chairman was approached by Paul Daw, a dowser who has made a study principally of stone circles, but who also has an interest in Neolithic monuments including henges and causewayed enclosures. He said that he had dowsed the site and could outline the henge; he was also willing to give demonstrations of the technique to the Group and to teach members how to dowse for themselves. He gave a talk to the Group on 16 March 2011, which I attended, followed by a practical session on 4 June, which I did not.

The talk given by Paul Daw was curious. He showed a lot of slides of scanned newspaper articles about his discoveries as well as some plans of the results of his dowsing. He focused largely on East Anglia (he is based in Cambridge) and on the Neolithic, particularly causewayed enclosures. However, at no point did he present any evidence that the sites he had discovered by dowsing had been confirmed by other techniques. In particular, there was no presentation of data derived from excavation. Allowing for his dowsing to have discovered buried anomalies, we were given only his assurance that they were of Neolithic date. I did not find this good enough to convince me and there were certainly others in the audience who felt the same way. Despite what readers may think, I had gone to the talk with an open mind and was prepared to be convinced. As an exercise in presenting a case for the reality of the technique, the talk was a failure.

I am less able to comment on the practical session, as I did not attend it. However, one of those who did managed to collect information about how the participants in the exercise perceived dowsing. They were asked before the fieldwork to rate how strongly they believed that dowsing could detect buried archaeological anomalies on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 for complete disbelief and 10 for complete belief. They were then asked again, after the fieldwork, using the same scale. In every case, the perception of dowsing improved after taking part. The average pre-fieldwork response was a rating of 2; after the fieldwork, it had risen to 8. This is an impressive improvement. Although no plans were made of the anomalies detected, blue flags were left in the ground to mark the positions of what was dowsed. There were two main groups of flags: a circular area, supposed to correspond with the position of the henge, and a linear ‘anomaly’ that I was told was very strong. The flags were still there when we began the 2011 season of excavation on 27 July.

This is where I can vouch for what was dowsed. There was a circle of flags in roughly the right place, although it was perhaps five metres too far to the south-east: it looked as if it had been put there by someone who knew roughly where the monument was located and roughly how big it was but not the precise location or size. This may be an unfair judgement on my part. However, when we opened up the trenches, it became even less clear what the flags were supposed to be marking: was it the inner ditch, the chalk bank or the outer ditch? The circle of flags corresponded with none of the archaeological features we excavated. Of course, one could always argue that as we haven’t yet excavated down to bedrock, the dowsing has detected a first phase that has not yet shown up. This would be special pleading and is not supported by the results of the geophysical survey or aerial photography.

The linear anomaly was even less convincing as an archaeological anomaly. It lined up perfectly on the tower of Baldock Church, just 910 m away to the east-south-east. For this reason, somebody suggested that it was a ley line. Well, ley lines don’t exist, despite the intuitive certainties of New Agers, so we can rule out that explanation! One thing that I did wonder was whether or not a twentieth-century ditch located in the 2010 excavation might have been the basis for this anomaly. The alignment was right, although its position was once again wrong, being about 15 m off the line of the archaeological feature. Nevertheless, nothing in the excavation corresponded with this anomaly.

If we treat the excavation as a test of the reliability of the dowsing, then the dowsing definitely failed. One of the real issues over the results that were obtained is that they were obtained with foreknowledge of what exists in this part of the field. I first published a plan of my suggested interpretation of the site as a henge in 2009 and there has been a page on the Group’s website giving details since February 2009. This means that anyone has access to information about the site, should they choose to seek it out; it is also the case that everyone who attended the dowsing session on 4 June had seen the site under excavation and had participated in the first season of work there. I could, uncharitably, argue that the dowsing was little more than a test of the memories of those taking part: the circular shape of the monument is known from a variety of sources, while the twentieth-century ditch, which ran roughly parallel with the footpath crossing the field, may have provided the “inspiration” for the linear anomaly. The details of the monument, which only became clear following the 2011 season on the site, were not picked up by the dowsing that preceded it. I wonder why.

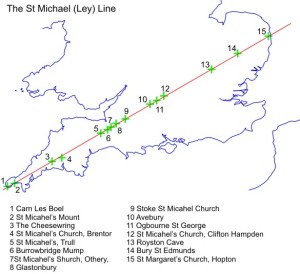

As a postscript to the dowsing of Stapleton’s Field henge, I was informed that it lies on the St Michael’s (Ley) Line, a notorious line said to run from St Michael’s Mount in Cornwall through to Hopton on the coast of Norfolk. It is supposed to be marked by a large number of churches dedicated to St Michael; it is also said to run through Royston Cave. Unfortunately, it doesn’t pass through any part of Stapleton’s Field, nor does it pass through Royston Cave, missing them both by about 3 km. This isn’t minor quibbling: 3 km is a long way off a line that’s supposed to be dead straight and accurate across hundreds of kilometres. Either sites that are supposed to provide evidence for it (such as Royston Cave) lie exactly on the line or they lie off it and must be discounted as evidence: you simply can’t have it both ways!

Dowsing as a technique

As the reader will have gathered by now, I am far from impressed by my encounters with dowsing on archaeological sites. On two occasions, I have seen it used in an attempt to locate archaeological sites whose existence was already known and on both those occasions, it failed to locate the sites with any accuracy. I may have been unlucky; I may have gained an accurate impression. But there is one more instance of a site I know that has been dowsed for information that I have deliberately held back from describing. It’s another site investigated by the Norton Community Archaeology Group, this time in 2007.

This attempt to dowse a site was very different. Based around the earthworks of part of the village that had been deserted during the Middle Ages, the dowser used a pendulum in an attempt to locate structures and date their abandonment. He also pointed to the locations of human burials, again supposed to be of medieval date. At the same time, a soil resistivity survey of the site was carried out. Although the geophysics was inconclusive, the dowser pointed to a number of buildings and graves and gave the dates (to the nearest year) of their demolition or burial.

This is the sort of technique that Tom Lethbridge believed could be used to identify different materials, date sites and even recognise abstractions. It is a long way from the use of a hazel twig or bent coathangers to locate buried anomalies, however they might be detected. Instead, the dowser has a more mystical role, tapping into data that simply cannot be encoded in a purely physical form. This is the realm of ‘subtle energies’ of which conventional science is ignorant. This sort of thing is removed from scientific testing: the basic principles on which it supposed to rely involve things that defy measurement. The nature of this type of dowsing is what Robert Sheaffer has described as a “jealous phenomenon”: one that disappears before conclusive evidence for its existence can be gathered. The phenomenon does not manifest itself, so the believers’ argument goes, in the presence of sceptics. This is the very essence of pseudoscientific thinking.

For this reason, I have no truck with the use of pendula on maps. There is nothing that can be tested. However, I am more open to the idea that dowsing might have some basis in reality. Might it be possible that the dowser is sensitive to gravitational or magnetic gradients in the landscape, such as might be produced by holes in the ground? Some dowsers have claimed that this is how the phenomenon works. That being the case, dowsers relying on changes in the background magnetism should be able to detect hearths, kilns, fired clay and ironwork; indeed, the magnetic signals should be so strong that they could swamp other signals. Yet dowsers generally seem to ignore such things. Why, if magnetism is the source of signals being picked up by the dowser, would the effects of these highly magnetic materials remain hidden? Then, if the dowser relies on an ability to recognise changes in the gravitational background, there ought to be a correlation between the size of a buried feature and the prominence given to in the results of dowsing. At Stapleton’s Field, the outer ditch of the henge – which geophysics indicates is at least 3.5 m wide – ought to be the most prominent ‘anomaly’ to be recognised in dowsing. Why, then, were the strongest responses received from a linear ‘anomaly’ that aligned on the (perfectly visible) tower of Baldock church yet did not have a buried correlate?

You can see where I’m going with this. Suggest a mechanism known to science that might explain how dowsers can get the results they claim, and there will always be something that doesn’t fit. If dowsers wish to explain the phenomenon using forces known to science, they then need to explain how the individual dowser can select from among the responses received to locate only those things that the person using the dowser wishes to find. Once they start to invoke forces unknown to science, we are in the realm of pseudoscience. The Bullshit Historian has done an extensive analysis of dowsing claims in archaeology and finds them wanting. So do I.

My methods of dowsing my series of ancient site from which i have retreived carved stone artifacts relates to triangulation in the form of a equalateral triangular grid that gets larger to encompass many stone sites in the pacific ,this grid can be formulated on globe ,linking many significant sites ..more than coincidence .Badger .H. Bloomfield .

LikeLike

You should accept James Randi’s $1 million challenge. It should be easy pickings for you.

LikeLike

A great read Keith, as you know I’m no Archaeologist, but as a big fan of rational thought it was a treat.

LikeLike

A superb piece, and admirably open minded too. I’d still like to have a go at it, just to experience the ideomotor effect. I’ve dug up a couple of interesting period comments on dowsing from the SciAm archive – I’ll stick them on my blog.

LikeLike

But I know that I’ll be accused of closed-mindedness and of being an agent of the accursed Randi!

LikeLike

Very well put, good sir. The prinicple of confirmation bias can go a long way in affecting people’s ability to think rationaly. I am a big fan of logic and common sense and it seems, at a cursory glance, that your wonderful blog does adequate justice to both. Kudos to you. I shall enjoy reading more from you in the future.

LikeLike

Field demonstrations such as described here are not a proper test for dowsing because you cannot eliminate the possibility that finds are made by means other than dowsing (e.g. prior knowledge, lucky guess). A double blind test as advocated by James Randi’s $1 million challenge is the only proper way. The fact that no dowser has been able to demonstrate under proper conditions the ability to find anything beyond what you could expect by chance alone speaks volumes about the veracity of the claims made by dowsers.

LikeLike

This is exactly the point I’m making with these two posts. Nothing that the dowsing supposedly “revealed” couldn’t have been guessed from the topographical clues. It was not a test. Double blind tests have failed time after time.

LikeLike

To clarify Keith’s last sentence, dowsers have failed time after time to demonstrate that they have any actual ability to find things when proper double-blind conditions are in place.

LikeLike

Sorry not to have made it clearer! I wasn’t as focused on writing as I should have been…

LikeLike

I’m not convinced dowsing works either, but for the sake of entertainment, let’s look to statistical algorithms. There are several randomized algorithms that solve well defined problems (almost certainly). Take simulated annealing. You sample random numbers from a distribution defined in terms of some function that, over time, evolves to have a narrow mode around the global optimum of said function (so that a randomly sampled instance is almost certainly the global optimum). Perhaps there is an analogy of dowsing to some random walk-type of algorithm. Unfortunately, I’m not terribly familiar with stochastic algorithms. Anyway, let’s suppose the dowsing stick is some sort of oracle distribution. The dowser samples directions from the stick so that eventually, with high probability, converges to an archeological site. Now, I imagine these sticks have to be specially crafted to find specific archeological sites. I can’t imagine a dowser able to find different sites with the same stick … or maybe the stick has modes for all archeological sites in the world.

That raises an interesting question: Can one craft a stick that, when wielded in a well defined way, finds a specific archeological site better than chance on average?

LikeLike

I think the answer should be yes. If we understand if and how a dowser chooses a direction based on the shape of a stick, then I imagine we could predict the shape of a stick so that the dowser’s choice is approximately the same as sampling a distribution with a mode around the optimal direction at, say, “most” positions in some area. But again, the stick “encodes” the position of the archaeological site which wouldn’t be known in advance anyway.

But that rests entirely on the assumption that the shape of the stick should somehow change the dowser’s search pattern. Does it?

LikeLike

It would be a darn lot easier if i just demonstrated to you how it is done!People are given these gifts and most of us accept them for what they are ,Nobody can get inside your head and tell YOU you are bullshitting ,just leave us alone! you guys think everthing has logic! you are so mistaken ,we just apply our gifts ..Wairua…for the good of humanity …not to bring forth Satan ..

LikeLike

had to smile when I saw the photo of you standing on a stone at stonehenge. Brought back memories for me – it was a standard school trip to go there (middle or primary school? I don’t remember) and I do also remember being able to climb on the stones while a lady gave us a lecture. Was back at Stonehenge just a few weeks ago with my family.. but not able to let them climb on the stones as I had done, of course. Still, they very much enjoyed it!

LikeLike

For what it’s worth, My father (a career science teacher) did an experiment with me in dowsing, when I was young. He had me hold two Coke bottles, each with a copper rod bent at 90 degrees nested in it, then had me walk across the yard. The rods crossed at one point. I repeated this walk several times, and got pretty much the same result: The rods crossed at the same point, every time. I knew nothing of dowsing at the time, and didn’t know that the rods were crossing at the point where the water main ran through our yard.

This, of course, proves little, as it is possible that some sort of sub-verbal cuing occurred. Still, I had no idea that the rods were supposed to cross at all, so I still wonder about that.

As I said, my experience proved little, and certainly doesn’t “prove” the wild claims of some dowsers and their backers. I’m just tossing it out there.

LikeLike

Could I use the map from this page of the line in a book I’m writing? is it yours? i’ll give you credit!

LikeLike

The map isn’t mine, I have to confess!

LikeLike