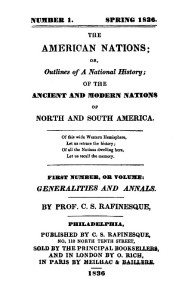

In 1836, a French scholar, Constantine Samuel Rafinesque (1783-1840), published the first of two volumes titled The American Nations: Or, Outlines of Their General History, Ancient and Modern, Including the Whole History of the Earth and Mankind in the Western Hemisphere, the Philosophy of American History, the Annals, Traditions, Civilization, Languages, &c., of All the American Nations, Tribes, Empires, and States. At the start of Chapter V, on page 121, he laments that “We have but few real American Annals, given in the original peculiar style” and goes on to list a few traditional accounts. On the next page comes a bombshell: “Having obtained, through the late Dr. Ward of Indiana, some of the original Wallam-Olum (painted record) of the Linapi tribe of Wapahani or White River, the translation will be given of the songs annexed to each: which form a kind of connected annals of the nation”. In other words, he claims to have obtained a document of prime importance for the early history of the Americas. He asserts that the people of North America “did possess, and perhaps keep yet, historical and traditional records of events, by hieroglyphs or symbols, on wood, bark, skins, in stringed wampuns &c.; but none had been published in the original form”.

He says in a footnote that “These actual Olum were at first obtained in 1820, as a reward for a medical cure, deemed a curiosity; and were unexplicable. In 1822 were obtained from an other individual the songs annexed thereto in the original language; but no one could be found by me able to translate them. I had therefore to learn the language since, by the help of Zeisberger, Hekewelder and a manuscript dictionary, on purpose to translate them, which I only accomplished in 1833. The contents were totally unknown to me in 1824, when I published my Annals of Kentucky; which were based on the traditions of Hekewelder, and those collected by me on the Shawanis, Miamis, Ottawas &c.”. Rafinesque proposes to place this newly translated record before the public.

The document Rafinesque revealed to the world is known as Walam Olum (also spelled Walum Olum or Wallam Olum), which allegedly tells the story of the Lenape people of an area known as Lenapehoking, now part of the north-eastern United States of America. According to Rafinesque, the Walam Olum consists of “3 ancient songs relating their traditions previous to arrival in America, written in 24, 16 and 20 symbols, altogether 60. They are very curious, but destitute of chronology. The second series relates to America, is comprised in 7 songs, 4 of 16 verses of 4 words, and 3 of 20 verses of 3 words. It begins at the arrival in America, and is continued without hardly any interruption till the arrival of the European colonists towards 1600. As 96 successive kings or chiefs are mentioned, except ten that are nameless: it is susceptible of being reduced to a chronology of 96 generations, forming 32 centuries, and reaching back to 1600 years before our era. But the whole is very meagre, a simple catalogue of rulers, with a few deeds: yet it is equal to the Mexican annals of the same kind. A last song, which has neither symbols nor words, consisting in a mere translation, ends the whole, and includes some few original details on the period from 1600 to 1820”. The songs were recorded as symbols on the bark, apparently a mnemonic writing system, with a total of 183 pictographs.

Rafinesque’s chronology, derived from assigning each named chief to a generation and assuming three generations to a century, is as follows:

About 1600 years before Christ passage of Behring strait on the ice, lead [sic] by Wapalanewa, settlement at Shinaki.

1450. Chilili leads them south, and the Tatnakwi separate.

1040. Peace after long wars under Langundewi at the land Akolaking.

800. Annals written by Olumapi.750. Takwachi leads to Minihaking.

650. Penkwonwi leads east over mountains.

460. The first Tamenend great king on the Missouri

60. Opekasit leads to the Mississippi.

About 50 years of our era, alliance with the Talamatans against the Talegas.

150. Conquest or expulsion of the Talegas.

400. Lekhihitan writes the annals.

540. Separation of the Shawanis and Nentegos.

800. Wapalawikwan leads over Alleghany mountains to Amangaki.

970. Wolomenap settles the central capital at Trenton, and the Mohigans separate.

1170. Under Pitenumen arrival of Wapsi the first white men or Europeans.

Here, at last, was an outline chronology for the pre-Columbian history of North America. Not only did it confirm that at least some of the Native Americans had arrived from Asia by crossing ice at the Bering Strait, but it also confirmed the story of Noah’s flood. Here was an indigenous American tale that linked its people with the Bible!

The initial reception of the Walam Olum

When Constantine Rafinesque first published The American Nations in 1836, it was largely ignored. His reputation had originally been as a botanist, although it had begun to suffer as accusations of monomania in constantly seeking new species were made against him (interestingly, his much criticised opinion that in botany “[e]very variety is a deviation, which becomes a species as soon as it is permanent by reproduction” was an interesting prefiguring of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection). His earlier foray into antiquarian speculation, Ancient Annals of Kentucky and Antiquities of the State of Kentucky (1824) was later criticised by Samuel Foster Haven (1806-1881), Librarian of the American Antiquarian Society, as unreliable.

Although critics found that the story appeared too be too good to be true, the general (if grudging) consensus of scholars was that Rafinesque had discovered a genuine and extremely important account of the history of the Lenape people. Its dissemination was largely accomplished through its reprinting and championing by the antiquary Ephraim George Squier (1821–1888) in 1849. Not everyone was convinced, though: the ethnographer Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (1793–1864) wrote to Squier expressing his view that the Walam Olum was a fraud. Despite this, the anthropologist Daniel Garrison Brinton (1837-1899) published a new translation as part of his The Lenâpé and their legends: with the complete text and symbols of the Walam Olum, a new translation, and an inquiry into its authenticity in 1885. Brinton concluded that it was a genuine text on the grounds that “what Rafinesque certainly had not the ability to do, was to write a sentence in Lenape, to compose lines which an educated native would recognize as in the syntax of his own speech, though perhaps dialectically different”. He concluded:

It is a genuine native production, which was repeated orally to some one indifferently conversant with the Delaware language, who wrote it down to the best of his ability. In its present form it can, as a whole, lay no claim either to antiquity, or to purity of linguistic form. Yet, as an authentic modern version, slightly colored by European teachings, of the ancient tribal traditions, it is well worth preservation, and will repay more study in the future than is given it in this volume. The narrator was probably one of the native chiefs or priests, who had spent his life in the Ohio and Indiana towns of the Lenape, and who, though with some knowledge of Christian instruction, preferred the pagan rites, legends and myths of his ancestors. Probably certain lines and passages were repeated in the archaic form in which they had been handed down for generations.

A study published by the Indiana Historical Society in 1954 with contributions by Charles F Voegelin, Paul and Eli Lilly, Erminie Voegelin, Glenn Black, Georg Neumann and Paul Weer, Walam Olum or Red Score: The Migration Legend of the Lenni Lenape or Delaware Indians attempted to bolster the claims for genuineness. Reviewers were not impressed and the issue remained controversial. In 1975, the Canadian artist Selwyn Dewdney (1909–1979) concluded in The Sacred Scrolls of the Southern Ojibway that the Walam Olum was a genuine birch-bark written record, but his work was not well received and he was accused of relying on outdated generalisations. In 1992, Joe Napora published a new translation, citing Dewdney’s work as an inspiration. However, by then, the story was unravelling.

Doubts grow

Early doubts about Walam Olum were based around Rafinesque’s inability to produce the original bark records and the failure to trace their background. The “late Dr. Ward of Indiana” from whom Rafinesque had allegedly procured the original records in 1822 proved impossible to identify, no-one of that name being registered as a doctor in the state in the early 1820s. Although Daniel Brinton acknowledged this, he managed to trace “an old and well-known Kentucky family of that name, who, about 1820 resided, and still do reside, in the neighborhood of Cynthialla. One of these, in 1824-25, was a friend of Rafinesque”. This is a desperate attempt to vindicate Rafinesque’s claim.

As anthropologists began to study the Lenape in the twentieth century, they found that it was difficult to confirm knowledge of the stories contained in the Walam Olum. In a study published in 1934, Erminie Wheeler-Voegelin (1903-1988), wife of the translator of the work in the 1954 Indiana Historical Society volume, was unable to point to any firm parallels between Rafinesque’s text and Lenape traditions. By the 1950s, scepticism had increased to the point where, in 1954, the anthropologist John G Witthoft (1921-1993) accused Rafinesque of plagiarising the Walam Olum from existing printed texts in the Lenape language and Lenape-English word lists.

By the last decades of the twentieth century, scepticism in the authenticity of Walam Olum had become the default position among anthropologists. However, it was the work of David M Oestreicher, an expert on the Lenape, that finally destroyed any lingering ideas that Walam Olum might be a genuine text (or at least contain genuine elements of Lenape tradition). Returning to Rafinesque’s manuscript, he noticed a curious feature that had not previously been remarked upon: although the English ‘translation’ was written out without alteration, Lenape words were sometimes crossed out and altered, usually to provide a better translation for the English words. In other words, this was not a Lenape text that Rafinesque had translated into English (which is what he claimed in his 1836 publication) but an English text that he had translated into Lenape. This is an utterly damning revelation.

David Oestreicher was also able to demonstrate that the date 1833 on the manuscript was itself fraudulent and that Rafinesque had worked on it between December 1834 and January or February 1835 in an attempt to win the Prix Volnay of the Institut Royal de France. The Institut had announced a prize for the answer to a specific question: Déterminer le caractère grammatical des langues de l’Amérique du nord connues sous les noms de Leni-Lenape, Mohegan et Chippaway (“to determine the grammatical character of the North American languages known by the names of Leni-Lenape, Mohegan and Chippaway”). To win the prize would have established Rafinesque as an historian and linguist of the highest order, after the poor reception of his Ancient Annals of Kentucky and Antiquities of the State of Kentucky. He backdated it to a time before the publication of some of the sources on which he had depended, to avoid accusations of plagiarism and forgery. His submission, Examen Analytique des Langues Linniques de l’Amérique Septentrionale, et surtout des Langues Ninniwak, Linap, Mohigan &c avec leurs Dialects ou Mémoir sur ces Langues & leur structure grammaticale (“Analytical examination of the Linnic languages of North America, and particularly of the Ninniwak, Lenape, Mohican etc. languages with their dialects, or, Memoir on these languages and their grammatical sturcture”), failed to win him the prize. Instead, the Prix Volnay went to Pierre-Étienne (Peter Stephen) du Ponceau (1760-1844), for his Mémoire sur le système grammatical des langues de quelques nations Indiennes de l’Amérique du Nord (“Memoir on the grammatical system of the languages of several North American nations”).

This was not the end of the story, of course. Having put so much effort into the composition of Walam Olum, Rafinesque seems to have been unwilling to let it disappear into obscurity and, as a result, he incorporated it into a work of history that ought to have set alarm bells ringing. His chronology includes the arrival of the first Europeans in North America c 1170, which is clearly meant to refer to the fictional story of Madoc, a supposed Welsh prince who has been claimed as a twelfth-century European voyager to North America. Discussion of the story of the “Welsh Indians” was current in the early nineteenth century and, around the time that Rafinesque was composing Walam Olum, had been completely debunked. A further element that ought to have been noticed but was not was the way in which Rafinesque blithely brought Atlantis into his discussion of migrations into North America. Despite all the tell-tale signs that Walam Olum was a product of a nineteenth century scholar of European origin, anthropologists and archaeologists were for too long unnecessarily willing to overlook them.

The Walam Olum today

While the Walam Olum is now considered by serious historians, anthropologists and archaeologists as nothing more than a literary curiosity of the early nineteenth century, albeit one with a baleful influence on the study of Lenape culture for the next century and a half, it is still discussed in New Age circles. New translations continue to appear and popular writers still lend it a credence it plainly does not deserve. Its story has been incorporated into the epic poem Brotherly Love by Daniel Gerard Hoffman (born 1923) that was turned into an oratorio by Ezra Laderman (born 1924).

One thing that is immediately striking about the story of Constantine Rafinesque and Walam Olum is its similarity to the story of Joseph Smith (1805-1844) and The Book of Mormon. In neither case could the publishers of these allegedly sacred texts produce any evidence that they had existed outside their imaginations; in both cases, the works explained the mystery of the peopling of the Americas that had inexplicably been overlooked in the Torah; in neither case does the work’s chronology match what can now be deduced using archaeological techniques. Although Rafinesque had denounced The Book of Mormon as a hoax, one is left wondering if its publication in 1830 had inspired Rafinesque in the methods of literary forgery. Like all such successful forgeries, it told a message that had willing listeners, confirming their beliefs and prejudices.

“One thing that is immediately striking about the story of Constantine Rafinesque and Walam Olum is its similarity to the story of Joseph Smith (1805-1844) and The Book of Mormon.”

Amen to that. The similarity struck in the first minute of reading about the Walum Olam.

LikeLike

“The way to make a million dollars is to start a religion.” – L. Ron Hubbard

LikeLike

There are TWO histories of America: The LENAPE history (800-1585) and the ENGLISH history (1609-present).

The LENAPE were Catholics, who spoke Norse.

They paddled into America from Greenland.

They were the Mississippian Culture.

The English historians suppressed knowledge of the Lenape by omiting the words “LENAPE,” “Catholic,” and “Norse” from the printing presses.

The LENAPE history survives as the “Walam Olum sacred texts” and as LENAPE LAND

(http://lenapehistory.blogspot.com/2012/09/lenape-used-boats.html),

which is a deciphered “Walam Olum.”

If your students do NOT learn that:

America has TWO histories,

the Lenape history is preserved as the Walam Olum, sacred texts,

when the English invaded, most Americans were Catholics, who spoke Norse,

and the 17th century English suppressed “Lenape.” “Catholics.” and “Norse” by omitting them from the printing press,

than YOU, too, are teaching an historical MYTH designed to suppress Lenape, Catholics, and Norse from historical knowledge.

LikeLike